When the wrong bat met the wrong pig,

in a world of our own making

In the late 1990s, the Nipah virus struck Malaysian pig farms, spilling over to humans and leading to disease and death. With increasing deforestation and habitat destruction forcing humans and animals into ever closer co-existence, its historical journey shows why we should all be worried about emerging zoonoses.

It was sometime in September 1998 when the first reports of a mystery disease killing pigs and humans began to surface from an intensively managed pig farm in Perak, a state in the northwest of Peninsular Malaysia.

Located in the district of Tambun, the infected farm – part of a larger pig-farming area – housed some 30,000 pigs. And spread among the farms in this area were more than 100 hectares of orchards, cultivated for additional income.

According to the local hunters and orchard workers that a team of Malaysian scientists would later speak to, pteropid fruit bats – also known as flying foxes for their long snouts and large forward-facing eyes – would swoop into the orchards at night to forage from the fruit trees, which had begun to offer a steady food supply in the face of increased destruction of their forest habitats over at least the previous decade.

The scientists noted that the pigsties on the infected farm were located close to mango, durian, rambutan and jackfruit trees – with their branches growing over the roofs of the pens, or stretching into them.

They also noticed that the pigsties, confined by low walls, extended beyond the edge of their roofs. This allowed the run-off of rainwater to bathe the pigs, but it also allowed the faeces or urine of bats, or partially eaten fruit containing their saliva, to collect inside the pens.

Unknown at the time, some of these bats were carrying a virus novel to humans. As ancient creatures that have existed for some 50 million years, these Pteropus vampyrus have evolved to become an efficient reservoir for a whole assortment of viruses without getting sick.

They are the only mammals that fly, and have evolved an immune system that tempers inflammation that could kill others.

On this farm, the virus found an opportunity to jump into pigs that came into contact with the bats’ excretions, or ate their discarded fruit.

As one scientist says to another in Steven Soderbergh’s 2011 film Contagion, which was inspired by this virus and gained new relevance during the Covid-19 pandemic: “Somewhere, somehow, the wrong bat met up with the wrong pig.”

Then, because the farm was so large and densely populated, the wrong pig spread it to another pig, and another, and another. The pigs fell sick, and when they coughed, making what was widely described as a “barking” sound, they passed the virus on to their human handlers.

The virus soon spread to other farms in the area – biosecurity measures were not generally practised in the region and it was normal to sell pigs between farms. Some farmers, hoping to cut their losses amid the fear and uncertainty, then sold sick pigs to farms in other parts of the country, transporting the virus some 300km (186 miles) south: to the village of Nipah, in the state of Negeri Sembilan.

Two decades ago, you would know you had arrived in Nipah because of the smell.

“The pig waste choked the water and killed all the fish,” says local politician and former insurance salesman Yit Lee Kok, who adds that, back in the day, half his clients were infected by the Nipah virus. “You closed your eyes and you knew where you were.”

Yit, 54, grew up in Nipah, which, he says, smells much better today. About an hour’s drive south of Kuala Lumpur, Nipah is a small grid of streets dotted with homes, a few shops and restaurants, and these days the atmosphere is languid.

In keeping with the fate of so many villages across Malaysia, most of the young have moved out to chase their dreams in the cities, leaving their elders to keep things running.

Yit says Nipah began as a “new village” in 1955, part of an effort by the then Malayan government and colonial British forces to cut off rural support for the Malayan Communist Party, drawing people out of the jungles by granting each family a house and three acres of land.

The core of Nipah’s history was its pig-farming industry, with most farms existing for two or three generations. By the late 1990s, the farms in Nipah and in its neighbouring village of Bukit Pelanduk had become home to the largest concentration of pig farms in Southeast Asia, rearing swine for local consumption and exporting to Singapore and Hong Kong.

Yit, whose father and grandfather were pig farmers, recalls how they were once so cash-rich that they would walk into the Mercedes-Benz showroom in Seremban, the capital of Negeri Sembilan, wearing just shorts and slippers, armed with thick wads of ringgit bills.

“Villagers’ lifestyle, you know,” he laughs. “A lot of them didn’t like to save money in the bank.”

Now, with pig farming banned in the state since the outbreak, the only reminders are a few empty pig pens, amid backyard chicken coops and rickety barns designed to attract sparrows for the cultivation of bird nests.

Villagers have taken to growing palm oil and dragon fruit, but these crops haven’t brought back the boom times.

These days, if you are passing through, you might visit the Nipah Time Tunnel Museum to learn about the rare but lethal virus, born of Pteropus vampyrus and Pteropus hypomelanus fruit bats, that put this village on the map.

These days, the cultivation of palm oil and dragonfruit has taken the place of pig farming in Nipah village, in the state of Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia.

Our present pandemic has shaken loose memories of just such zoonoses: diseases transmissible from vertebrate animals to humans. Covid-19 is believed to have originated from wild horseshoe bats, possibly spread through a captive pangolin sold at a wet market in China, though consensus remains elusive.

During these Covid years, we have also been reminded of bird flu, Sars, Mers, Ebola, Zika: all infectious diseases originating from wildlife, spread directly to humans or indirectly through intermediate hosts such as farmed animals, vectors like mosquitoes or the consumption of contaminated meat.

Compared with these epidemics, the Nipah surge was modest, though it has killed about 640 people in Southeast Asia since 2001.

It is lesser known, like the Marburg virus, Rift Valley fever, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever or Lassa fever. But all are on a list of viral pathogens deemed a top research priority by the World Health Organization (WHO), in part because there are no commercially available vaccines or antiviral drugs to fight them.

Scientists have found evidence of Nipah in pteropid bats throughout their global range, which includes Southeast Asia, South Asia, Australia, East Africa and islands in the Indian Ocean and western Pacific – and these bats can spread the virus over vast distances.

Lab investigations have also shown that the virus is capable of infecting a wide range of animals, including cats, mice and non-human primates, increasing the possibilities of intermediate hosts that could spread it to us.

Though Nipah has not reappeared in Malaysia since 1999, there have been multiple outbreaks in the region.

In Bangladesh, where outbreaks have occurred nearly annually since 2001, fruit bats have transmitted the virus directly to humans by contaminating their food, feeding on raw date-palm sap collected in pots and hung from trees overnight, which villagers then consume fresh in the morning.

And unlike in Malaysia, human-to-human transmission is common, which partly explains the higher fatality rate of 70 per cent in Bangladesh, compared with 40 per cent in Malaysia.

Recognising the potential time bomb Nipah could pose, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), a global non-profit organisation that coordinates and finances development of vaccines for diseases that might have pandemic potential, has signed a US$25 million contract with two American biotech companies to hasten the development of a vaccine against the virus.

Pau Jeou Ching at the Sungai Nipah Time Tunnel Museum in Nipah village, in the state of Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia.

In 1999, Pau Jeou Ching was 14 years old and could often be found helping out at his father’s pig farm in Nipah after school. The family business, founded around 1980, spanned two acres of land occupied by 1,000 pigs.

Pau began to see signs of sickness in his family’s and their neighbours’ pigs in mid-February, during Lunar New Year. At the time, the Nipah virus had not yet been identified, and they watched with trepidation, having already heard of the misfortune that had befallen pig farms up north, in Perak.

Besides the telltale cough, which could be heard from some distance away, the symptoms varied depending on the pigs’ ages – but among them were breathing difficulties, foaming at the mouth, trembling and twitching, seizures and paralysis. Some were found running repeatedly into fences.

Days after the festive season began, hospital admissions grew. Pau soon heard of people dying every day. Then, he and his father were both struck by the virus.

Pau’s father was admitted to the University Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC), in Kuala Lumpur, while Pau followed five days later; they were among the first patients there.

Both initially presented with a high fever and headache – other patients reported breathing difficulties, coughing, muscle aches, vomiting – but Pau’s father became disoriented and then fell into a coma.

Many patients had respiratory symptoms, but the virus mainly attacked the central nervous system, causing severe encephalitis – swelling of the brain.

In early March, three days after he arrived at the hospital and eight days after the onset of his symptoms, Pau’s father died. He was 53 years old.

After spending two weeks in hospital, Pau went on to make a full recovery, evading the residual neurological problems that plague other patients.

“The last time I saw my father was on the day before he was admitted,” says Pau. After that, “he was in a more serious state in the ICU and I was in a different ward, so we didn’t see each other.”

He only learned of his father’s death from his aunts after he was discharged.

At the time, the government was still treating the disease as Japanese encephalitis – usually spread by mosquitoes – as antibodies related to it were found in some patients.

Thousands of vaccines had been rushed in to inoculate farmers before sending them home. Villages were heavily fogged with insecticides. But people continued to die.

Some experts, such as Tan Chong Tin, a neurologist at UMMC, were unsure about the government’s verdict.

“We didn’t know what it was,” he says, “but we realised it was related directly to the pigs. So we quietly told the relatives, ‘Come on, get out of the place.’ And I think that helped save some lives.”

By the end of March 1999, most of the farms in Nipah and Bukit Pelanduk – 300 to 500 small-scale family farms, each rearing between 50 and 3,000 pigs, according to Pau – had been contaminated.

“All the pig farms around here were very crowded,” he says. “So when one of them was infected, the virus spread to the others very fast. The virus was uncontrollable.”

Unlike the pig farms in Perak, which were relatively distanced from each other, those in Nipah and Bukit Pelanduk were highly concentrated, with neighbouring farms less than 100 metres (330 feet) apart.

Many were located among residential homes, and the lack of biosecurity measures and poor animal husbandry methods also helped spread the virus. Some farmers used the same needles to artificially inseminate different sows, for instance.

All this made it easy for infection to spread between pigs and then to people. Soon, farmers were forced to abandon their farms.

Some surrendered their pigs to the Department of Veterinary Services to be “depopulated”, while others took the monetary incentive and did the killing themselves.

Some pigs escaped the farms and roamed the villages and nearby oil palm estates looking for food. The stench grew from decaying carcasses later discovered in vacated homes.

Amid the confusion, Chua Kaw Bing, then a junior virologist at the University of Malaya, was about to defy his superiors. Like Tan, he did not think the disease was Japanese encephalitis.

In early March, he surreptitiously isolated the virus from the cerebrospinal fluids of infected patients and ran tests. What he saw made his heart skip a beat. He told his superiors it was likely a novel virus, but was discouraged from pursuing his inquiry any further.

He felt there was an institutional bias to confirm the diagnosis of Japanese encephalitis.

Still, he persisted in his attempts to persuade his superiors and was finally given the green light to fly to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, as local facilities were inadequate for studying the virus further.

On March 12, after obtaining a US visa within 24 hours, he packed the virus in his carry-on luggage and boarded a plane. In a personal account published in 2004, Chua – who declined to be interviewed for this story – recalled that when he examined the virus under an electron microscope at the CDC, he immediately recognised the “concrete ring-like” structures he saw.

He telephoned his head of department back home immediately, telling him: “Prof, listen! Listen carefully! Under the electron microscope, the virus has the morphology of a paramyxovirus, but not JE. For God’s sake, please do not talk about Japanese encephalitis any more.”

Paramyxoviruses include highly infectious viruses such as those that cause measles and mumps, and primarily spread via respiratory droplets.

Declared to the public on March 20, the novel virus was named Nipah, after Pau’s village, from which it was first isolated. What had begun as a relatively small outbreak in Perak just months earlier had by now spread not just to Negeri Sembilan, but also to the neighbouring state of Selangor.

It had also spread to an abattoir in Singapore that had imported live pigs from an infected farm in Malaysia.

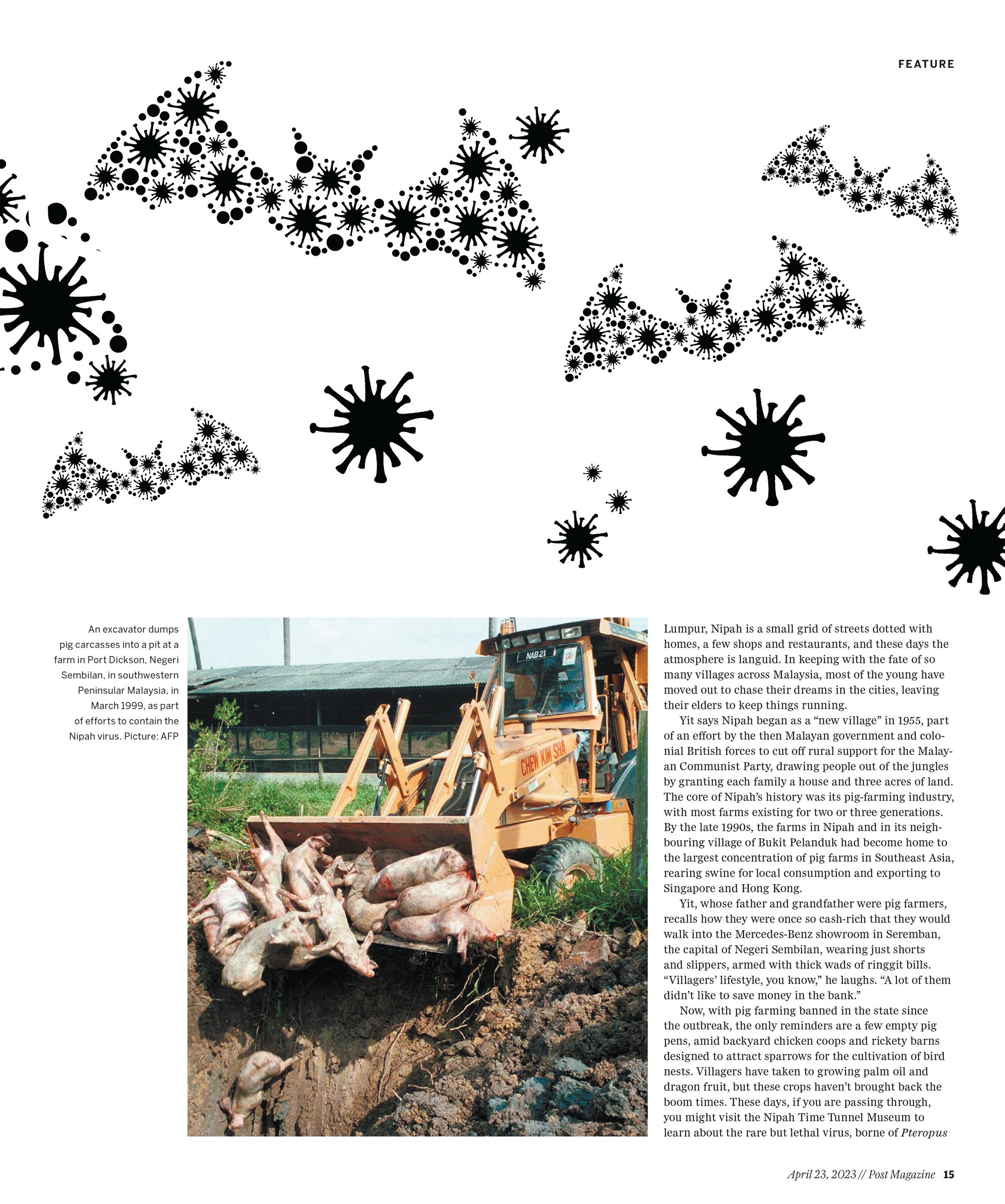

Armed with knowledge of this new virus, the Malaysian government, with the help of international experts, banned the movement of pigs and began culling all pigs on infected farms as well as those within a 10km radius. The animals were shot then buried in deep pits.

All in all, about 1.1 million pigs from 900 farms, which represented about 45 per cent of the national pig population, were destroyed.

“In one night we lost everything,” Pau says. But he felt numb at the time, mourning the more profound loss of his father.

He has since moved out of Nipah and owns a business selling party accessories, but he continues to take appointments with anyone who wishes to visit the Nipah Time Tunnel Museum, which he helped to establish.

The last human case of Nipah was reported on May 27, 1999. The mystery had finally been solved, but those Lunar New Year festivities had come to a tragic end.

By December, 283 people had been infected, and 109 had died. Negeri Sembilan shouldered the brunt of the outbreak, counting 231 infections and 86 deaths.

“All living things – mammals, reptiles, whatever – have their own microbiome, right?” says Latiffah Hassan, a veterinary and epidemiology expert and a coordinator at the Malaysia One Health University Network. “They all have combinations of microbes that are naturally in them. Humans, too.

“We have tons of bacteria and protozoans and all that living in our skin, in our gut. Most of them do not cause any harm [when they cross species], but of course some can become pathogenic.”

Of the millions of microbes that exist, roughly 1,400 – which include viruses, bacteria, fungi, parasites – are pathogens that have the potential to harm humans, according to a United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report published in 2020.

The Neolithic Revolution, at the end of the Ice Age some 10,000 years ago, marked a significant new chapter in the history of zoonoses.

Humans, who had until then lived in nomadic hunter-gatherer communities, began to form settled agricultural communities to cultivate crops and domesticate wildlife, creating new spaces where humans and animals lived in close proximity, allowing pathogens to move from animals to humans more often.

The larger human congregations also allowed diseases to spread more widely.

The bubonic plague, influenza, smallpox, measles, cholera: these are some of the oldest zoonoses the world has known. And measles, thought to have spilled over into humans from cattle in the 10th century, casts a long shadow.

When Europeans arrived in the Americas in the 16th century, they brought it and other infectious diseases with them, which are believed to have wiped out 95 per cent of the indigenous population, leading to the destruction of their ancient civilisations.

Measles still causes epidemics globally today, infecting about 30 million people and killing more than 2 million each year, according to the WHO.

It had taken hundreds of thousands of years for humanity to grow to 1 billion people, in 1800. Now, there are nearly 8 billion.

This population explosion, followed by rapid urbanisation and growth of industry, has wrought drastic changes on our landscapes – particularly the deforestation that has encroached on and destroyed wildlife habitat.

The UNEP report points to the increasing demand for meat, agricultural intensification, and the consumption and exploitation of wildlife as the most important human behaviours driving the emergence of zoonoses globally.

“The number-one driver of epidemics of zoonotic disease outbreaks is us – the things we are doing that influence the way we come into contact with wildlife and the way that our livestock comes into contact with wildlife,” says Jonathan Epstein, a veterinarian and disease ecologist at EcoHealth Alliance, a global non-profit organisation that works to safeguard animal and human health.

Before the Nipah outbreak, Malaysia enjoyed decades of economic growth. From 1960 to 1990, the urban population nearly doubled.

Vast tracts of forests were burned, logged and replaced with new towns, rubber and palm oil plantations, and farms, shrinking the habitats of wildlife, as well as pteropid fruit bats.

“Ipoh was growing into some of these more forested areas, so there were a lot of forest edges where these bats would live and come to forage in the villages,” says Epstein, who had visited the capital of Perak and its surroundings to investigate the origins of the outbreak.

Chua has also hypothesised that the haze that routinely blankets Southeast Asia due to widespread burning of forests – which might have been exacerbated by droughts caused by El Niño events – could also have led to the fruiting failure of remaining forest trees, dwindling the bats’ food supply.

Naturally, the bats would have been forced to seek greener pastures. And in Perak, in 1998, they found them in the side-hustle fruit trees among the pig farms. Both pig and mango production reportedly tripled in Peninsular Malaysia between the early 70s and late 90s.

“Cultivated fruits are a reliable food resource that these bats learn to exploit over time,” says Epstein. “These bats live up to 20-plus years in the wild, so they have a memory of where they find food at different times of year.”

And once a virus makes its way into the crowded conditions of an intensively managed animal farm, things can take a grim turn.

“What has consistently been shown is that if you didn’t have enough pigs on a farm and enough new pigs being born continuously, the virus would quickly fizzle out. Pigs would get infected, they would recover and it would go away. It wouldn’t support an outbreak,” he adds.

Since 1990, deforestation has been responsible for the loss of an estimated 420 million hectares of forests worldwide, an area roughly the size of the European Union.

Globally, 90 per cent of deforestation is attributed to agriculture, including the planting of crops for both human and animal consumption, as well as the clearing of forests for animal grazing. Farmland now makes up half the world’s habitable surface, while forests make up about 38 per cent.

At the same time, these forces are also driving biodiversity loss and climate change, and Epstein believes we should be talking about all three issues together.

Agriculture is the leading driver of biodiversity loss globally, threatening the existence of 86 per cent of endangered species.

At present, just 4 per cent of the world’s non-human mammals are wildlife; 60 per cent are livestock, providing an abundance of possible hosts for zoonotic disease.

Agriculture also accounts for a quarter of total global greenhouse gas emissions, accelerating climate change. This, in turn, can exacerbate disease risk and biodiversity loss in an ever destructive feedback loop.

The Hendra virus, a close cousin of Nipah, offers a parallel example of some of these dynamics. It first emerged in Australia in 1994, and is believed to have originated from black flying foxes, which then spread the virus to racehorses grazing in paddocks contaminated with the bats’ excrement; the horses then spread it to their human trainers.

Since then, the virus has emerged more than 60 times in the country, killing more than 100 horses and four out of seven humans infected.

As with Nipah, deforestation coupled with climate-linked food shortages has driven the bats into human habitats, where food is readily available.

Then, once an infection takes hold, anywhere in the world – and if it assumes the capability for human-to-human transmission – our ever more globalised trade and travel can create greater potential for pandemics.

Earlier epidemics or pandemics happened two or three times per century, but we have had several major outbreaks in the past two decades, and 75 per cent of all emerging infectious diseases since 1970 are zoonotic.

“Zoonotic diseases have always been with us,” says Chong, the neurologist. “There’s nothing unusual about zoonosis. It’s human lifestyles that have changed.”

Scenes today from the village of Tanjung Sepat, in the state of Selangor, Malaysia.

The Nipah outbreak left Malaysia’s pig industry in shambles.

According to correspondence with Malaysia’s Department of Veterinary Services (DVS), there were 1,774 pig farms with a population of 2.35 million pigs in the country before the outbreak, with nearly a million being exported.

In 2000, the number of farms had dropped to 783 and the pig population to 1.4 million. About 17,900 workers in pig breeding and supporting industries such as pig feed and oil and fats production were affected. The export of live pigs, once a lucrative market, dried up.

Though farmers here have managed to avoid another Nipah outbreak – by distancing their farms from residential areas by at least 200 metres and refraining from planting fruit trees on pig farms – the country’s pig industry has never fully recovered. Today, Malaysia has about 1.3 million pigs on 443 farms.

In 2017, the export of live pigs finally resumed, to Singapore, but only one farm in the country – in Sarawak, designated by the World Organisation for Animal Health as an area free from foot and mouth disease – has been licensed to do so.

A pig farmer who prefers to be known simply as Yee used to operate a farm in Tanah Merah, a few kilometres from Nipah and Bukit Pelanduk. During the outbreak, he remained on his farm and waited.

“It wasn’t clear what it was or how it spread or what would happen,” he says in Mandarin. “The situation was really bad. Nobody wanted to buy our pigs. Nobody wanted to eat pigs.

“If we kept feeding the pigs we would lose money, and feed suppliers didn’t want to give us credit. So we fed the pigs with cheap food, like leftover bread.”

In late March 1999, when the discovery of Nipah was announced, the government ruled that along with those on infected farms, pigs on all farms within a 10km radius also must be culled.

Though his farm was not infected, Yee lost more than 2,000 pigs. Some farmers had protested the culling, but Yee did not. He was afraid for his life, and just hoped that farmers would be financially compensated. They were, though for less than what the pigs were worth.

After the outbreak, Yee didn’t work for about a year. He tried raising cattle, then ducks. It didn’t work out, and he decided to try his hand at pig farming again.

He rented a farm and purchased 1,000 pigs in the coastal village of Tanjung Sepat, in the state of Selangor, bordering Negeri Sembilan; it was the closest area where pig farms already existed.

According to the DVS, “The Nipah outbreak was a lesson learned for most pig farmers in Malaysia. Most farms nowadays have a minimal biosecurity system, with at least control of vehicle movement and reduced visitation.”

Yee and other pig farmers declined a request to visit, citing concerns about the African swine fever – which doesn’t infect humans – that first struck Malaysia in 2021.

Yee has since rented another plot and bought 2,000 more pigs, employing five workers. Other pig farms in the area – perhaps 100 to 150, he says – are small like his, with up to 3,000 pigs each.

But pig farmers make up a small proportion of the population in Tanjung Sepat. Most here are fishermen, and in recent years they have complained of dwindling catches due to seawater pollution attributed to pig farms.

To reduce the risk of disease infiltrating a farm, the DVS said that it has been encouraging farmers to adopt what it calls “modern pig farming” methods, with pigs raised in enclosed buildings equipped with proper ventilation, temperature regulation, and waste management systems. Only 23 farms in the country have complied.

In some states, such as Perak, farms have been threatened with closure if they don’t convert to closed-house systems, but Yee says farmers in Selangor haven’t yet been given the ultimatum, and he is still farming using traditional methods.

It is worth noting that in some other parts of the world, closed-house farming is considered the conventional method. Seen strictly from a disease standpoint, it makes implementing biosecurity measures easier, while other considerations – such as animal welfare, which could also impact animal health – may speak more for free-range farming systems.

“Some of these things are at odds with each other and have to be thought about and reconciled,” says Epstein.

For pig farmers in Malaysia, the hurdles are economic.

“In Tanjung Sepat, pig farming is still done mainly for subsistence,” says Yee. “I am renting the land, and we don’t know how long the government will let us farm pigs, so we don’t dare put money into setting up modern infrastructure facilities.

“If you want to change to a modern pig-farming system, the investment is very high, and there is too much uncertainty about the future.”

Other pig farmers in Peninsular Malaysia surveyed by a team of Malaysian scientists in 2019 expressed similar concerns. They were reluctant to make the change while it was unclear if their licences would be renewed, if continued urbanisation near their farms would lead to complaints and shutdowns or if their quotas of pigs would be insufficient to earn back their investment.

In a majority-Muslim country, many pig farmers, mostly Chinese, also worried about socio-religious sensitivities – Muslims don’t eat pork – and whether political change would shift support for their industry.

“I’m thinking of closing up this business,” says Yee, who also feels hampered by the inability to export his pigs. “The past few years, we keep losing money and losing money, and the government didn’t really help us.”

It’s predicted that future pandemics are likely to be zoonotic in origin and caused by viruses. At present, nearly 1.67 million undiscovered viruses may exist in wildlife, of which some 631,000 to 827,000 have the potential to spill over into humans.

One of these diseases may turn out to be “Disease X”, an enigmatic-sounding place holder for any as yet unknown virus that would have epidemic or pandemic potential.

Scientists around the world, such as those with the Global Virome Project, have been working to identify viruses that could be the next Disease X.

According to the scientists, virus spillover will most likely emerge in forested tropical regions with dense populations and high wildlife biodiversity, and where there is a high rate of land-use change, such as in Asia and Africa.

Climate change, too, could drive more than 15,000 new cases of mammals transmitting viruses to other mammals over the next 50 years, as species move to cooler places and meet for the first time, opening up new pathways for new viruses to spread to humans.

Warming temperatures could also amplify mosquito-borne diseases and spread them to new regions.

Latiffah, the veterinary and epidemiology expert, says that for Malaysia, the priority isn’t blanket surveying of wild animals for potential emerging viruses – though work on that in the country is being done with international funding.

“I think for countries with fewer resources, we should focus on prevention and surveillance by addressing the root causes.”

She points to zoonotic malaria in Malaysia as receiving particular attention from international researchers.

Originating from macaques, Southeast Asia’s most abundant non-human primates, and spread by mosquitoes, zoonotic malaria has superseded human malaria in the country, prolonging Malaysia’s efforts to eradicate the disease in the country by 2020.

It is particularly prevalent in Sarawak, where deforestation for logging and oil palm plantations has brought macaques closer to human settlements, to which they adapt quickly.

According to a recent study by Harvard University researchers, 3.3 million people are expected to die each year from viral zoonotic diseases.

The minimum estimated value of these lost lives is US$350 billion while the value of direct economic losses is US$212 billion, based on an analysis of all new viral zoonoses that have emerged since 1918. Prevention would cost 5 per cent of the value of lost lives and less than 10 per cent of the economic losses.

In light of all this, what is really needed, many experts say, is a transformative change in how we live and a more holistic outlook on zoonotic disease.

As propounded by the One Health approach, it is time to recognise – beyond lip service – that our health is inextricable from the health of animals and nature. None can be pursued in silos, especially in light of recent outbreaks of H5N1 bird flu and G4 swine flu that scientists worry have the potential to infect humans and cause the next pandemic.

As the memory of Covid-19 fades, it feels like we’re all impatient to get back to life as it was, to forget about what brought it into existence in the first place.

It is comforting to tell ourselves that another epidemic or pandemic won’t hit while we are still not out of the woods with this one, that zoonotic spillover is a rare event.

But as Epstein reminds us, “We only hear about the ones that do happen, and have some impact. We don’t have a good measure of all the times a spillover has happened that hasn’t resulted in an outbreak.”

And the next time, we might not be so lucky.